Object Of The Month

5th January 2026

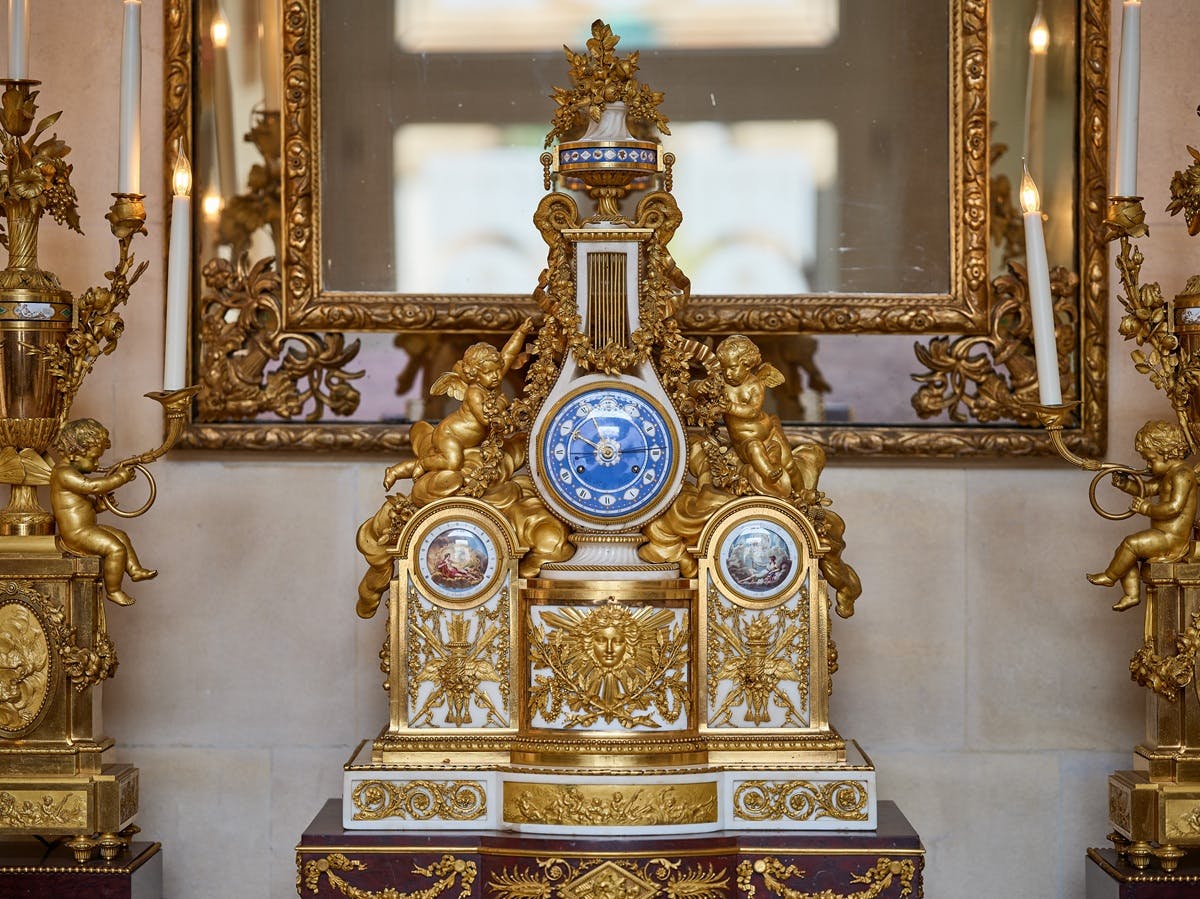

Ormolu and Enamelled Clock, New Front Hall

The transition to a new year is a universal and ancient moment for reflecting on the passage of time. This beautiful, ornate clock, which stands in the New Front Hall, presents an opportunity to pause and appreciate the transient nature of moments past and those yet to come.

Meet the object

This ormolu, enamel and marble clock dates to the early nineteenth century. ‘Ormolu’ is a technique of gilding bronze that was incredibly popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Here, it particularly shines in all the fine detail: the longer you spend looking at this clock and the matching candelabra, the more details you spot. The clock itself is shaped like a lyre, a musical instrument with classical origins that is famous for being associated with the Greek god Apollo. There are so many sculpted flowers, two ram heads either side of the top, as well as sunbursts, putti and even some snakes.

Not only does this clock tell the time, but it also indicates the weekday, date and month, as well as the passage of the sun and the moon. If you look closely at the clockface, a ring inside the hour numbers indicates the day of the week, and a ring outside the hours shows the numerical date. At the top of the clock, above the ram heads and on a rotating disk also enamelled in blue, are the names of the calendar months. Both the months and days of the week are written in Spanish.

Either side of the main clock are dials showing the passage of the sun and the moon. On the left is the sun, with a painted god who is likely Apollo. He wears a laurel wreath and holds a lyre – Apollo’s symbols – and, amongst many other things, was a sun god. On the right are the phases of the moon, indicated with a goddess, likely Apollo’s sister Artemis, who had a connection with the moon. Artemis’s symbols in Greek mythology were normally a bow and arrow, as well as a crescent moon, both of which this delicately painted deity has.

Clock makers and enamellers

This clock also tells us much about its making. On the face, it is signed De Belle à Paris, referencing the clockmaker Jean François de Belle. De Belle became a master watchmaker in 1781 and was active in Paris in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

In tiny writing, at the very base of the clock face, we can learn the enameller. Here, it is signed Dubuisson f.1802. Dubuisson was the name artist Étienne Gobin went by. Gobin was formerly a porcelain painter who had spent time employed at Sèvres, the most celebrated porcelain manufacturer in France. At Sèvres, he was a flower painter, and the delicate floral and celestial details on the clockface exhibit this talent.

A Napoleonic connection

This beautiful clock was made for Joseph Bonaparte (1768-1844), brother of Napoleon (1769-1821). Napoleon was the second of eight surviving children, and Joseph was his older brother. Both brothers left Corsica to be educated in France.

As the Napoleonic Wars raged on, Napoleon – by now, Emperor Napoleon – installed his older brother as King of Naples and Sicily in 1806 until 1808. Joseph then became King of Spain as José I. He was much more unpopular in Spain compared to his reception in Naples and Sicily and ended up abdicating after the French defeat at the 1813 Battle of Vitoria. Following the final defeat and exile of Napoleon in 1815, Joseph settled in New Jersey in the United States. Later, in the 1830s, he returned to Europe, spending time in both England and Italy.

He eventually passed away in Florence in 1844 and was initially buried at the Basilica of Santa Croce before being moved to Les Invalides in Paris to be interred alongside his brother.

Passage to Bowood

The clock found its way into the collection at Bowood after it was purchased by Margaret Mercer Elphinstone, Comtesse de Flahaut (1788-1867), in Paris in 1830. Margaret and her husband Charles, Comte de Flahaut (1785-1870), were the parents of Emily, the 4th Marchioness of Lansdowne (1819-1895). Not only this, but the Comte de Flahaut had been Napoleon’s aide-de-camp, accompanying him on his later European campaigns.

Emily inherited and brought this and other notable Napoleonic items which can still be seen at Bowood.

Image: Jean-Baptiste-François Bosio, Portrait of Joseph Bonaparte, n.d. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain image.