Object Of The Month

19th November 2025

Marble Specimen Table

The beauty of the collection at Bowood is how diverse and intriguing it is. Every object has a story and introduces us to a fascinating period of history, and our November object is certainly no different in this regard.

Meet the object

If you have visited us before, you may have noticed this colourful marble specimen table upon entering the Orangery. Bought by the 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, it represents an intersection between classical antiquity, Continental European and British Imperial manufacture and 18th and 19th century cultures of collecting.

What exactly is a specimen table? It is a decorative object that is made up of numerous different specimen materials. In our case, 170 different samples of marble sit in beautiful rings on this Italian tabletop, showing different veins and textures, from mottled greens to bright yellows, rich reds to a deep blue.

It is a spectacle of colour and pattern if you look closely, and we can identify most of the specimens through a key that lists (almost all) the types of marble.

We know that Henry, the 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne (1780-1863), purchased the tabletop in Naples in 1812.

Lord Lansdowne and collecting

Across successive generations, the Lansdowne family have been incredibly interested in art, architecture and collecting.

The 3rd Marquess was an integral part of this family activity. Some of the highlights in the Bowood collection today that were gathered by Lord Lansdowne include many of the books in the Library, the paintings in the Orangery – both old masters and contemporary commissions – and the stunning group of Richard Parkes Bonington (1802-1828) drawings on display in the Top Exhibition Room.

Lord Lansdowne succeeded to the title in 1809, upon the death of his half-brother, John, 2nd Marquess (1765-1809). He had already spent time travelling in Europe, and would do so again, purchasing art both at home and abroad.

His travels in Italy not only added to the collection at Bowood but also transformed how the estate looked. The Upper and Lower Terrace Gardens were built to remind him of Italy.

Naples in the early nineteenth century

Lord Lansdowne was not the only eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century traveller enthralled by Italy and its art, architecture and history.

Italy became one of the most important stops of travellers in the eighteenth century, particularly young men on the Grand Tour, the original gap year taken before settling into their responsibilities. Cities like Venice, Florence, Rome and Naples were chosen because of the opportunities they afforded to get close to the history of the ancient Romans and the marvels of its Renaissance. Plenty of digging and dealing happened as archaeological excavations uncovered spoils of worlds gone by, with wealthy travellers clamouring to purchase these items from unscrupulous sellers so that they might display a piece of the classical world at home.

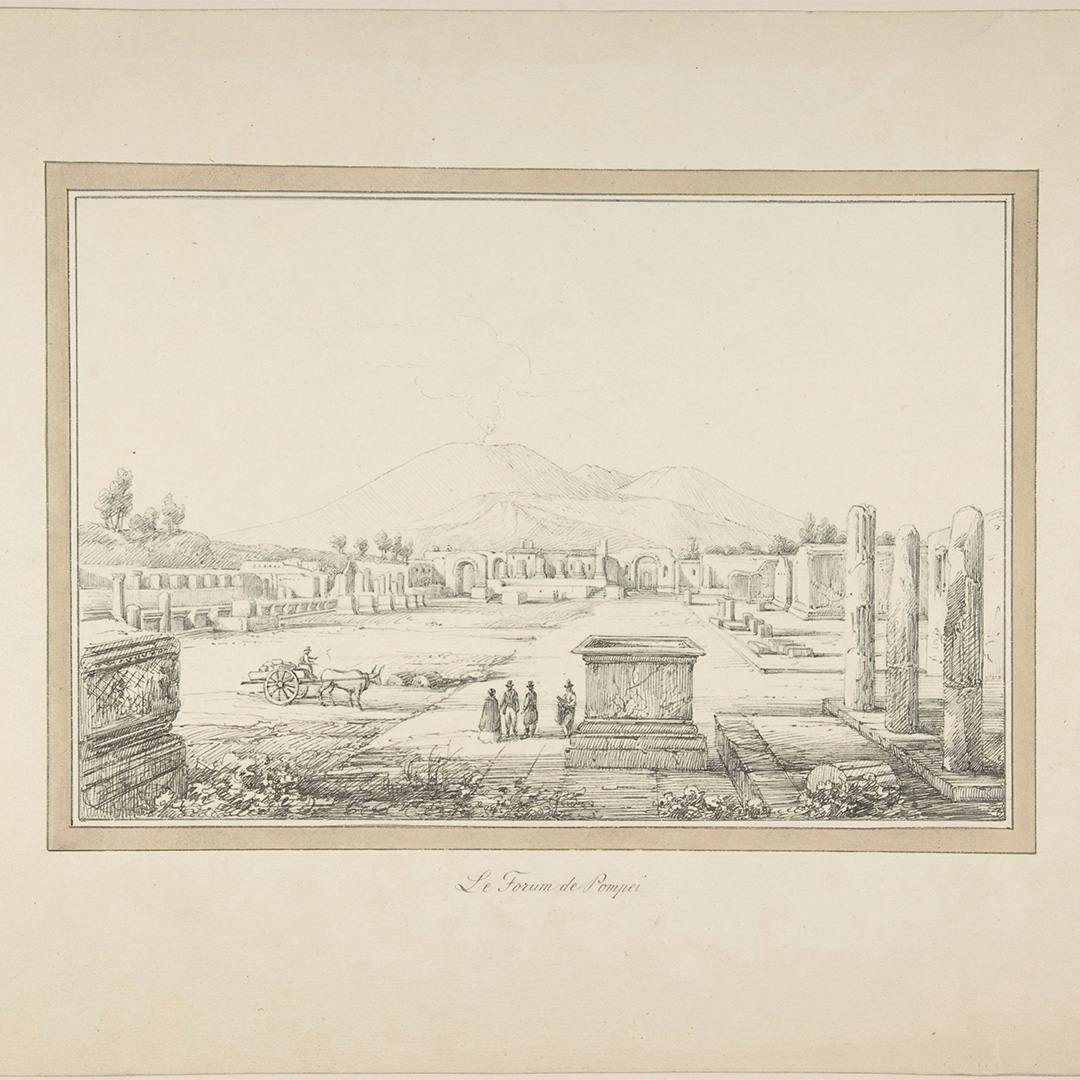

Naples, where this tabletop was purchased, was exciting because of its proximity to Pompeii and Vesuvius. Work began on uncovering Pompeii in 1748, with plenty of artefacts and wall paintings removed across the decades, and many visitors opting to see the site and feel close to an ancient world stopped in its tracks by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. Vesuvius remained active during this time, providing extra fascination for visitors.

Even though the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) significantly slowed travel to Italy and the continent, some intrepid travellers made it through and brought back items like the Bowood specimen marble tabletop.

Image: Anonymous, View of Pompeii, 19th century. Open access image, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 35.37.6.

A piece of Italy at Bowood

Tables like this were popular souvenirs to bring back. The various types of marble could come from excavations, monuments, historical sites and decorative stone that many stonecutters would have had to hand in their workshops. Most often they came with a key to distinguish the specimen types, and the bases were added once the tabletops had made the journey home. The base of this table is made from early nineteenth-century mahogany.

Specimens provided a connection to not only the historical world but the natural world too through the specimens on display, enabling their owners to gain knowledge about a place and share it once they were home. Lord Lansdowne had a great political career, and surrounded himself with artists, writers and intellectuals, driven by a keen curiosity to learn about the world around him. This table would have undoubtedly been part of that love of knowledge.